Market Dominance Puts Some Health Care Organizations Under a Microscope

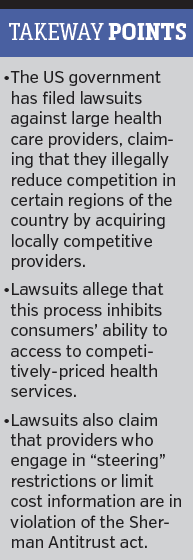

In North Carolina, the state’s attorney general filed a civil suit in June against Carolinas HealthCare System (CHS), alleging that it “illegally reduces competition in the health care market in [the city of] Charlotte and limits consumers’ ability to shop around for better deals on health care.” The case was jointly filed with the US Department of Justice (DOJ).

In North Carolina, the state’s attorney general filed a civil suit in June against Carolinas HealthCare System (CHS), alleging that it “illegally reduces competition in the health care market in [the city of] Charlotte and limits consumers’ ability to shop around for better deals on health care.” The case was jointly filed with the US Department of Justice (DOJ).

The legal complaint alleges “that CHS acted unlawfully to preserve its dominance in the Charlotte health care market,” according to a release from North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper’s office. “To protect its revenues… CHS aggressively uses its market power to keep consumers from taking advantage of better prices at other hospitals and from getting access to less expensive insurance policies.”

CHS has denied any wrongdoing. When contacted, Kevin McCarthy, media relations manager for CHS, referred to the organization’s official statement and had no further comment.

“We have neither violated any law nor deviated from accepted health care industry practices for contracting and negotiation,” notes the statement.

Concerns about Transparency, competitor steering

The lawsuit claims that “CHS blocks consumers from receiving information about the costs and quality of CHS services, critical data that could potentially help consumers find quality care at better prices.”

In response, CHS said in its statement that they are “strongly committed to providing accurate and useful information to consumers and patients as it relates to cost, quality, and overall value of the care they receive.”

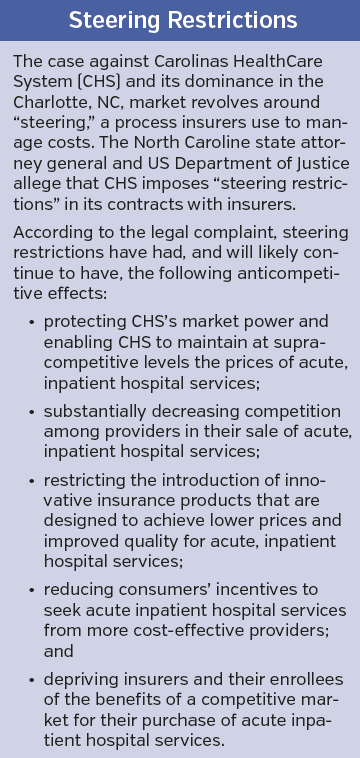

The suit also alleges that CHS restricts the insurers it contracts with from allowing its competitors to use the practice of “steering,” a method that enables consumers to reduce health expenses. Steering can occur via tiered networks that place physicians who offer higher quality at lower cost in top tiers. Patients who use these physicians pay less out of pocket. Narrow-network plans are another steering tool that enable consumers to pay less if they choose from a smaller network of providers.

According to the legal complaint, “CHS has gained patient volume from insurers steering towards CHS, and has obtained higher revenues as a result. CHS encourages insurers to steer patients toward itself by offering insurers modest concessions on its market-driven, premium prices.”

While there is nothing inherently wrong with that strategy, according to the complaint, “CHS forbids insurers from allowing CHS’s competitors to do the same. By restricting its competitors from competing for—and benefitting from—steered arrangements, CHS uses its market power to impede insurers from negotiating lower prices with its competitors and offering lower-premium plans.”

CHS’s contracts with insurers either forbid steering outright or allow CHS to terminate agreements when insurers engage in steering with CHS competitors, according to the complaint.

Additionally, according to the lawsuit, CHS places restrictions on insurers that hinder their ability to provide accurate information about the cost and quality of CHS services vs those of the competition. These “restrictions on… price and quality transparency… prevent patients from accessing information that would allow them to make health care choices based on available price and quality information.”

The state and DOJ believe that both the steering restrictions and limits placed on dissemination of information are in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Continued on next page

The New Normal?

The New Normal?

A spokesperson in Mr Cooper’s office said that “the next step involves CHS answering the complaint, followed by the discovery phase.”

As the state of North Carolina and the DOJ wait for CHS to respond to the civil action, it seems to be a good time to ask if this is the new normal. That is, are health care organizations that are already large, or trying to get bigger via acquisitions or consolidation, opening themselves up to greater scrutiny as a result?

It seems so, though it is difficult to determine if it is a simple consequence of increasing size and consolidation or whether government officials are targeting organizations in response to the public’s frustrations with rising health costs.

By insisting that its contracts are legal, CHS seems to be implying that the free market is working in the Charlotte area; however, the government disagrees.

In the end, the reason for the amplified scrutiny hardly matters; the fact is that it’s here, and perhaps here to stay. Furthermore, this issue is larger than just CHS and the Charlotte area.

Other organizations are increasingly dominating major health care markets; for example, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) is the undisputed leading health care provider in Western Pennsylvania. According to Standard & Poor’s profile of UPMC from 2015, the health care system “continues to maintain a dominant provider presence in Western Pennsylvania.” Furthermore, UPMC recently merged with smaller entities and has even entered markets in Western New York State and Northeastern Pennsylvania.

Other organizations are increasingly dominating major health care markets; for example, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) is the undisputed leading health care provider in Western Pennsylvania. According to Standard & Poor’s profile of UPMC from 2015, the health care system “continues to maintain a dominant provider presence in Western Pennsylvania.” Furthermore, UPMC recently merged with smaller entities and has even entered markets in Western New York State and Northeastern Pennsylvania.

“I think what you’re seeing in North Carolina goes on in other parts of the country,” notes a clinician, who requested anonymity because of his ties with specific organizations mentioned in this story. “I really don’t think that [CHS has] done anything different than what these other large systems have done.”

Although UPMC has not been accused of preventing steering, it has been under the microscope in the past. According to local press reports, in 2010 it was accused, along with insurer Highmark Inc, of developing anticompetitive agreements and keeping national carriers out of markets in the Pittsburgh region. A suit was dismissed in 2013 but recently reemerged, forcing UPMC to reach a tentative settlement for $12.5 million. In late July, a federal judge indicated that she plans to approve the settlement.

It’s Complicated

In 2015, Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen Kane tried to block UPMC’s merger with Jameson Health in New Castle, PA, out of concern that the deal would increase health care costs and decrease access to competitive health services in the region; however, in May of this year, an arbitrator allowed the deal to proceed.

UPMC’s acquisition of Jameson Health illustrates the complicated nuances of such mergers. While allowing UPMC to get larger—and perhaps drive up medical costs—the deal also provided the struggling Jameson Health system with a much-needed infusion of $85 million in funds, according to local press reports.

The merger also gives residents in the New Castle area continued access to health services. In fact, it is possible that New Castle might gain access to better quality care given UPMC’s investment in Jameson, $10 million of which is going to physician recruitment.

According to the clinician who requested anonymity, while the benefits of such a deal are apparent, the level of scrutiny is not surprising, no matter where it occurs.

“State governments are supposed to protect their citizens,” the clinician said. “In that sense, it is appropriate. I imagine the citizens of Charlotte are happy that the state is looking at [CHS].”