Experimenting With Nonmedical Benefits to Improve Outcomes

Health care in the United States has long been defined by its focus on disease and illness. Americans use health care services when sick, and insurers pay for services to diagnose and treat signs and symptoms of disease. What is covered by most private and public insurers are services directly related to these medical needs.

What the US health care system does not primarily focus on, is how to maintain and improve the health of individuals through services that are not directly linked to a medical need. In 1948 the World Health Organization provided a definition of health that to this day is not fully realized in the United States. It defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

However, some payers in the United States are waking up to the need to look more closely at what health means and how to achieve it, partly and largely driven by the unsustainable cost burden of health care.

Provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that provide incentive for providers and payers to focus more on prevention have also driven more payers to experiment with new ways to define the medical benefit.

“A lot of the policies and payment structures in the ACA are aimed at paying providers to keep people healthy,” J Mac McCullough, PhD, MPH, assistant professor at the School for the Science of Health Care Delivery at the College of Health Sciences at Arizona State University, Phoenix, said in an interview.

New payment models in the ACA, such as value-based payment models, are spurring the current interest in focusing on people’s health, Dr McCullough explained.

“To do that, it is not enough to only provide medical care. Often time we have to go broader or further upstream,” he said.

Finding ways to keep people healthy has urged payers to cast a wider net to capture needs related to health that go beyond the direct medical needs of patients. Into this net are what are referred to as social determinants of health—things like housing, transportation, access to good food, and education.

Emerging data show that health utilization and outcomes do improve when these social determinants of health are addressed. Recent data from a 2018 study in Population Health Management looked at the effect of a program developed and implemented by a managed care organization (MCO) to coordinate medical and social services for its Medicaid and Medicare members.

The researchers found that the medical costs for members who received needed support in barriers to housing, transportation, and food were 10% lower than for members who did not receive such services.

Focus on Housing

Among the many social determinants of health, perhaps none is seen as more critical than stable housing.

“Housing is the big one,” Dr McCullough said. “It makes a huge difference in what you can do for patients when people are in stable housing versus when they are not.” Citing the example of patients with diabetes, he emphasized that without access to refrigeration there is no place for people without housing to store their insulin.

In recognition of this critical connection between housing and health, several pilot programs around the country are looking at ways of providing housing to those who need it. UnitedHealth Group is one of several payers who are actively collaborating with local nonprofits and other groups to design and implement programs aimed at subsidizing housing for members in need.

“Since 2011, UnitedHealthcare has invested more than $350 million to help finance and build 54 affordable-housing communities in 14 states, creating more than 2700 new homes,” Tyler Mason, vice president of communications at UnitedHealth Group told First Report Managed Care. “Our investments have been focused on new communities with innovative onsite programs such as support services and case managers to help residents access health care, job training, education, child care, and other programs to improve their lives.”

Speaking at a recent UnitedHealth Group investor conference, Phil McKoy, chief information officer, United HealthCare Services, underscored the commitment by the organization to address housing and other social determinants with the aim at addressing the needs of the “whole person” and particularly those who are most vulnerable. In particular, he spoke on how the organization is using data on members to target those with specific needs.

“Basic needs must be met, such as food, housing, and transportation, before we can influence better health,” he said. “We take disparate sets of data from the services provided to an individual, including social services, and we aggregate and enrich them to create a holistic view of the person.”

“With this insight, we can guide them to the full spectrum of community services and support that will help keep them independent and healthy,” he added.

Whether such efforts will pay off is suggested by data coming in from other pilot housing projects underway. Jennifer Forster, director of Medicaid Strategy at HMS Eliza, highlighted several programs, including one in California, showing that providing permanent housing support for the 10% of homeless people in Los Angeles with the highest cost needs resulted in a more than 70% reduction of total health care costs per person.

Further evidence, she noted, included data from a pilot project in Hawaii in which medical costs of homeless patients dropped by 43% within 6 months of securing housing and supportive services. Data from another pilot project showed that a $1.6 million investment by a Florida hospital in a program that placed chronically homeless persons in housing with extensive support services resulted in avoiding an estimated $2.5 million in medical care for just six high health care utilization patients.

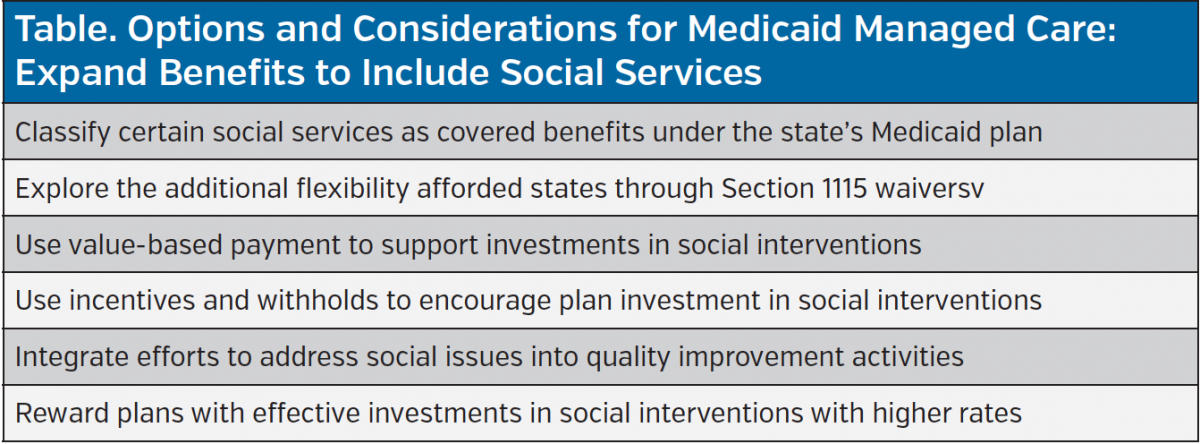

In recognition of the social determinants of health that particularly affect vulnerable populations, and with the expansion of Medicaid under the ACA, increased attention is being given to how managed care organizations that largely manage Medicaid can address these issues. A report issued in January 2018 by the Commonwealth Fund listed a number of strategies (Table).

Challenges Ahead

As is true of any complex problem, addressing social determinants of health as an integral part of delivering health care is difficult and challenging. Ms Forster broke it down into three main challenges: (1) identifying people who are facing socioeconomic barriers to care, (2) addressing the cost of providing extra services particularly for health plans that serve Medicaid and dually-eligible persons, and (3) figuring out how to coordinate services.

“This is a multifaceted problem that will require a series of interventions on behalf of health care providers, plans, and community resources to identify, intervene, and track results,” she said.

Looking at this with a wider lens, Dr McCullough emphasized two main challenges that are not unique to this issue but relevant. Both have to do with asking payers and providers to go outside what traditionally has been their arena of focus. Because some of the benefits of stable housing, for example, will not only benefit the health of a person but may also lead to other benefits such as better schooling and ability to get and keep a job—should an insurer be asked to incur the cost?

“Is it really fair for a health insurance payer to have to pay for the health that other entities and agencies benefit from,” Dr McCullough asked. Referred to as the “wrong pocket program,” this challenge basically asks one entity to bear the cost of a service/practice without expecting to receive commensurate benefit from that cost.

Another challenge, Dr McCullough explained, can be what he calls “mission creep.”

“We’re already asking a lot of providers and at some point we probably are going to be maxing them out,” he said. “We have to be careful not to be asking health care providers to assume responsibility for so much of a patient’s life that it becomes overwhelming.”

According to Melissa Andel, MPP, vice president of health policy at Applied Policy, these challenges may mean that payers and providers are not the best conduit for serving social determinants of health.

“I am not sure health plans are the ideal or most efficient way to deliver these services,” she said. “Within health and medicine, so many things that seem intuitive or a ‘slam dunk’ have turned out to not have the impact that people assume they would have.”

Ms Andel underscored the need for more population-based health studies to evaluate the real benefits of these types of programs, and cautioned against relying on anecdotal stories. However, she also pointed out limited data has not hindered approval of coverage for more traditional medical services.

“We use drugs and medical procedures that perhaps have the same amount of limited data on effectiveness,” she said. “Drugs are approved based on surrogate endpoints, surgeries are performed with limited data.”

What remains to be seen is if efforts to address the social determinants of health within the health care system itself—by providers and payers—can improve health outcomes and reduce health care utilization, and, if so, can be sustained and scaled up.