Debate Over Health Plan-Driven Clinical Pathways Continues

Is the debate over payer-driven oncology clinical pathways subsiding—or has it not yet hit its stride? Looking to California might lead you to believe the issue is dead on arrival. There, a bill that would have prohibited health insurance plans from developing and implementing clinical care pathways in the state was quietly shelved. However, 3000 miles away in Connecticut, things seem to just be getting started: a similar bill in the state employs a different method to restrict clinical pathways and has a much greater chance of passing.

Is the debate over payer-driven oncology clinical pathways subsiding—or has it not yet hit its stride? Looking to California might lead you to believe the issue is dead on arrival. There, a bill that would have prohibited health insurance plans from developing and implementing clinical care pathways in the state was quietly shelved. However, 3000 miles away in Connecticut, things seem to just be getting started: a similar bill in the state employs a different method to restrict clinical pathways and has a much greater chance of passing.

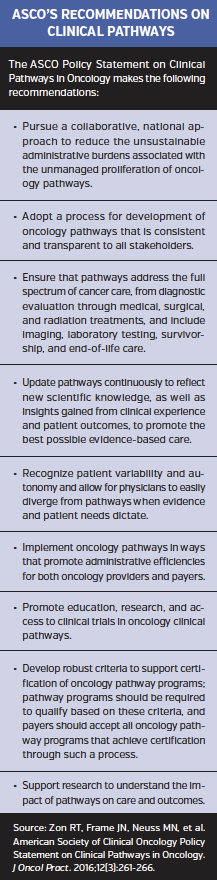

Meanwhile, on the national level, the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates has lent its support to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s (ASCO) position on clinical pathways, which focuses on making sure all patients are treated appropriately and reducing the administrative burden of navigating multiple pathways.

People on both sides of the controversy over payer-developed clinical pathways say that they are looking out for the best interests of patients. There are those who think insurance-driven plans focus too much on cost, reduce patient and physician autonomy, and overly complicate the process of providing care. Others contend that not allowing input from those who are footing the bill will prevent pathways from meeting their intended aim—improving the overall value of care—and assert that the best pathways are collaborations between health care providers and payers.

Despite the disagreement, many within the managed care field have expressed concern over legislating clinical pathways, arguing that this matter should be left to payers and health care providers to resolve.

A Bill Dies in California…

In California, Assembly Bill 2209 is dead—at least for this year. The bill would have prohibited health insurance plans from developing and implementing clinical care pathways in the state beginning next year. The bill’s sponsor, Assemblywoman Susan A Bonilla, believes that health plans are often too driven by cost to develop pathways that are focused on quality care, and she sought to limit pathway development to provider groups and hospitals.

But her attempt failed. According to Estevan Santana, Ms Bonilla’s legislative aid, the bill is not moving forward. Furthermore, Mr Santana told First Report Managed Care exclusively that the assemblywoman does not have plans to pursue the policy this year.

One of the groups opposed to the bill, the California Association of Health Underwriters (CAHU), believes that the bill would have discriminated against plan-driven pathways, despite the fact that the jury is still out on all pathways, payer and otherwise. CAHU pointed to a report commissioned by the state legislature, which states that “the available evidence is insufficient to conclude that [pathways] are more effective when implemented by providers than by plans or insurers.”

Even though insurers are breathing a sigh of relief in California, supporters of the failed bill haven’t given up hope. Nichole A East, executive manager of the Medical Association of Southern California, said that even though AB 2209 is a “dead bill” and will not moving forward this year, “[we are] continuing to assess next steps on the issue of clinical pathways.”

…Another Rises in Connecticut

And then there is Connecticut state Senate Bill (SB) 435. The intent of this bill is the same as its California counterpart; however, the bill employs a different method to restrict the use of clinical pathways.

Dawn Holcombe, executive director of the Connecticut Oncology Association, helped author the Connecticut bill. When asked about the California legislation, she explained that it was based on state-specific regulations governing health maintenance organizations (HMOs). “Their bill focused more on California law that positions insurers as corporations, which put clinical pathways development out of their scope of services.” In other words, it contends that the process constitutes corporate practice of medicine.

The Connecticut bill has a much different focus, said Ms Holcombe. It is aligned much more closely with the ASCO Policy Statement on Clinical Pathways in Oncology (J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(3):261-266).

When Ms Holcombe and colleagues started writing SB 435, “[they] knew the ASCO position paper was coming,” she said. “We took a similar approach. We believe that pathways are an important consideration in the management of oncology whether you are a physician or a payer, but there have to be certain parameters in place when choosing one pathway vs another,” Ms Holcombe said. “This is particularly important for the patient and physician.”

Pathways Too Narrow

The Connecticut bill was written assuming that insurers would want to consider pathways and would only apply when an insurer has decided to utilize pathways, according to Ms Holcombe. “It does not in any way prohibit insurers or physicians from utilizing pathways but sets boundaries as to their design and use.”

According to testimony delivered by Ms Holcombe during a public hearing earlier this year, the Connecticut bill “will set forth expectations of transparency and appropriate clinical evidence and process for the use of clinical pathways by an insurer.” The legislation will also “define that any clinical pathway programs that an insurer uses… must give preference to those developed by that specialty’s medical community and be published following explicit standards.” Finally, “the costs of health care for patients and the health care community [must] not be increased by redundancy if a creditable clinical pathway is already available.”

The bottom line, Ms Holcombe said in an interview, is that “clinically appropriate standards” are set to address the “significant variation in the design” of clinical pathways.

“There are clinical pathways created by the medical community that usually are vetted by hundreds of physicians on a number of committees for each disease,” she said. “Then there are pathways developed by commercial organizations for or with private insurers, brokers, or employers. They tend to have a narrower approval process and lack extensive academic vigor and rigor.”

According to Ms Holcombe, the two gold standards for oncology clinical pathways are the Value Pathways powered by NCCN—developed in a collaboration between McKesson Specialty Health, the US Oncology Network, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)—and Via Pathways from Via Oncology, which were originally developed for providers in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center health system. “Each provide transparent clinical pathways vetted by over 500 academic and active clinical physicians in the specialty,” noted Ms Holcombe in her testimony. “Both sets are universally available to every oncology practice and center in the United States and [are] being embedded in the predominant electronic medical records systems utilized in oncology.”

Too Much Deviation?

Too Much Deviation?

Supporters of the legislation believe that guidelines implemented by payers are “not transparent, have been created by an external for-profit vendor, and are approved by a handful of paid physicians,” according to Ms Holcombe. “They appear to deviate as much as 20% to 30% from clinical pathways embraced by the treating medical community.”

For this reason, SB 435 also attempts to halt the practice of compensating physicians. Ms Holcombe stated: “Such payments may sometimes be called a management fee, but it truly isn’t if it [is paid based on] choosing one treatment over another. That is a shortsighted process that misses the true depth and value of the provider’s oncology management.”

She contrasts this with the oncology management fee associated with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Oncology Care Model, which covers oversight and management for every patient under active chemotherapy treatment “regardless of what treatment is chosen.

“It is inappropriate to link a specific payment solely for choosing a specific treatment,” continued Ms Holcombe. “It doesn’t look right to the patient, it doesn’t look right to the physician, and it certainly doesn’t make the physician or the insurer look good to the patient.”

Ms Holcombe noted that “clinical pathways may well be one of many tools utilized together by payers and providers to enhance oncology medical decision-making, but physicians and their medical specialties should create evidence-based, transparent clinical pathways, and insurers should support and encourage [their] use as part of appropriate medical decision-making.

“Working together and jointly supporting a clinically vetted, medical decision-making process that balances population trends with individual patient needs is quite different than simply publishing selected preferred treatments for populations of patients,” she said.

“No Ability to Control Cost”

Some express concern that legislation to regulate pathways like the Connecticut bill is likely to leave those who are footing the bill out of the process. Winston Wong, PharmD, president of W-Squared Group, who is widely known as the developer of the first plan-derived clinical pathway program for CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield, counts himself among those ranks.

“I find the Connecticut bill to be very one-sided and onerous to the point that it would result in [payers having] little or no ability to control cost or standardize care,” he said.

Dr Wong noted that the bill requires each clinical pathway to be accepted by clinicians, professional societies, medical institutions, patients, patient advocacy groups, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device manufacturers. “Under this approval process, you will never get any pathway program approved,” he predicted. “Patient advocacy groups are totally against the pathway concept. So are the drug manufacturers, particularly if they are not on the pathway.”

Furthermore, Dr Wong pointed out: “Nowhere are the financial stakeholders included.” Gary Owens, MD, president of Gary Owens Associates, and a First Report Managed Care Editorial Advisory Board member, agrees. He stated that all stakeholders, including insurers, should have a say in designing pathways and that a balance must be maintained between access to care and cost.

The Connecticut bill contains provisions designed to protect providers from being forced into making clinical decisions that they do not believe are appropriate. Dr Wong said that such assurances already exist. “Every program and every health plan has an appeals process, where medical justification can be provided for virtually anything. Plus, state insurance regulations allow for appeals.”

He acknowledges that the process can be time-consuming but believes such efforts need to be made to justify cost in certain outlier situations. Moreover, provider appeals are very likely to be granted. Dr Wong noted that the denial rate is less than 5% for Humana’s pathway program.

Regarding insurers making payments to providers in order to incentivize adherence to clinical pathways, Dr Wong pointed out that this is similar to what the CMS is proposing with the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) created under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which will make incentive payments to clinicians for following treatment protocols based on quality and cost.

“It seems that the Connecticut bill [is challenging] the CMS philosophy,” he suggested.

Ms Holcomb disagrees, noting that the Connecticut bill will result in “a value-driven project that differs from other CMS initiatives like the MACRA and MIPS programs.”

Dr Wong also questioned the requirement to disclose such financial arrangements, calling them “proprietary,” and adding that disclosure “inhibits the system and process of maintaining competitive rates.” He also added that disclosures “will do nothing but add to the patient’s already high stress level from receiving cancer treatments.”

In response, Ms Holcombe pointed out that “patient advocacy groups in Connecticut were quite involved in the bill’s language regarding disclosure of fees.”

Dr Wong concluded: “If it is acknowledged that clinical decisions are made in the best interest of the patient, and there is a process in place to appeal decisions, there is really no need for… onerous red tape.”

Just the Beginning

Government overreach is also a concern for payers. Dr Owens said that he feels the state bills are well-intentioned but worries that due diligence might be lacking.

“Basing legislation on a few anecdotal cases may solve the problem for a few and create far more sweeping issues in the future if increasing cost becomes a societal and patient challenge,” he said.

Norm Smith, president of Viewpoint Consulting, Inc, added that he does “not think that state governments are equipped to make these complex medical decisions.”

Those who disagree are pushing forward. Connecticut has a limited session this fall; however, Ms Holcombe expects SB 435 to be considered early next year. She added that this might just be the beginning of a nationwide push for clinical pathway reform.

“This is an issue of significant concern across the country that is not going away,” she said. “There are a number of state and national associations that are looking at what is being accomplished in California and Connecticut, and you are very likely to see more of a full court press coming very soon.”

What Payers Can Do

Despite their distaste for legislative restrictions regarding clinical pathways, many payers acknowledge that insurers can do more to improve the way in which pathways are implemented.

Regardless of the controversy, insurers should be closely examining their pathways, stated Dr Owens. “They should be looking at pathways continuously to make sure they are evolving with the rapidly-changing science behind oncology treatments.”

While he questioned the feasibility of implementing ASCO’s recommendations across competing payers, Dr Owens agreed with ASCO’s goal of ultimately arriving at a standardized process supported by evidence and concurs that it would reduce the administrative burden for providers.

Mr Smith boiled the issue down to its practical essence. “Pathways are roadways; they provide general direction. When the roadways become [the] absolute [route], never allowing for deviation, something is not right,”he said.

Mr Smith’s advice to insurers is to examine pathway programs to make sure they don’t always point to older medications.

“I am uncomfortable when I see all pathways leading to lower-cost treatments with older products,” he said. “All new therapies can’t always be inferior to older therapies. That would mean that pharma and biotech are very unproductive, which is very unlikely.”

Mr Smith stated that if the evidence supports an alternative therapy, then “it should never be a problem” to use it. Over time, data will allow the medical community to see clearly which segments of the population will benefit most from particular therapies, he said.

Dr Wong asserts that the two state legislative proposals miss the mark on having providers and payers work together to develop and implement pathways, emphasizing that not all pathways developed within the practice are based on evidence and free from bias. “I’ve seen and heard of in-practice pathways being built upon the practice’s purchasing contracts,” he said. “The pathway development process needs to be collaborative.”

The bottom line, said Dr Wong, is that if a pathway is not appropriate, the provider should avoid it. This leads to an important distinction between mandatory pathway programs vs opt-in. “I can see a provider rebelling against a mandatory program, but if they elect to opt-in, they should do so with full knowledge of what the consequences and benefits are.”

Mr Smith urged payers to understand that, for better or worse, “doctors have egos, and pathways conflict with those egos. They do not want others telling them what to do.”