California Bill Falters Amidst Drug Price Transparency Dispute

As massive price spikes on both new and well-established medications have shoved the rising costs of prescription drugs into the national media spotlight, the growing movement to rein in health care expenditures by dealing with the cost of medication has started to gain traction.

Drug costs make up roughly 10% of overall health care spending and about 19% of costs for employer-sponsored health plans, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. A recent Wall Street Journal report indicated that total spending on prescription drugs in the United States rose 12.2% to nearly $425 billion in 2015.

“A famous health economist once described hospital pricing as chaos behind a veil of secrecy,” said Kristof Stremikis, MPP, MPH, senior manager for policy at the San Francisco-based Pacific Business Group on Health, which represents the health care purchasing decisions for some of the largest employers in the United States. “Looking at pharmaceutical drug spending over the last couple of years, I would say it’s chaos behind a veil of complexity.”

The $1000-per-pill price tag set by Gilead Sciences for its hepatitis C drug Sovaldi caused an uproar as it put a strain on public health care budgets. Furthermore, plenty of attention and frustration was stirred up when Turing Pharmaceuticals bought the 62-year-old drug Daraprim (pyrimethamine; Turing) and inflated the per pill price from $13.50 to $750, an overnight increase of 5000%.

Reactions to drug price increases from health care payers, doctors, and patients coupled with criticism from politicians has led to various attempts to curb price hikes and spending while lifting the veil, so to speak, via legislation. Vermont passed the nation’s first drug transparency law earlier this year, and several other states, including California, have considered similar proposals.

Transparency Bill Killed

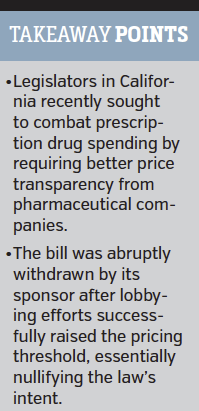

California’s recent Senate Bill (SB) 1010 would have required drug makers to provide advanced notice to insurance companies, pharmacy managers, and state agencies that purchase prescription medications before implementing hefty price hikes. The bill would have also required health insurance companies to identify the drugs driving health care spending by reporting data to state regulators, including the portion of premiums attributable to pharmaceuticals.

California’s recent Senate Bill (SB) 1010 would have required drug makers to provide advanced notice to insurance companies, pharmacy managers, and state agencies that purchase prescription medications before implementing hefty price hikes. The bill would have also required health insurance companies to identify the drugs driving health care spending by reporting data to state regulators, including the portion of premiums attributable to pharmaceuticals.

A broad coalition of business and labor groups, health plans, provider groups, and others threw their support behind the bill in the hopes that the advance notice would give the government, insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers a chance to negotiate.

Arguments against the measure came largely from the pharmaceutical industry, including the California Life Sciences Association (CLSA) — a trade group for biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies. The organization claimed the bill’s requirement for advance notice could encourage large pharmacies or purchasers to stockpile drugs in order to avoid higher prices—a scenario that could leave smaller, independent entities unable to acquire the drugs needed.

CLSA president and CEO Sara Radcliffe argued that most price increases have actually been offset by discounts, rebates, and other payments by drug companies to pharmacy benefit managers and insurance companies. These are dollars, she pointed out, that are held onto instead of being passed along to patients in the form of lower prices or premium reductions.

After passing the full Senate in June and clearing the Assembly Health Committee in August, SB 1010 ran into difficulties in the Assembly Appropriations Committee, where it passed only after substantial amendments were made that weakened its intended effects.

The changes raised the threshold for price increase notification from 10% to 25%. They also removed the mandate to provide justification of those cost hikes and delayed the implementation date for the notification requirement. In response, SB 1010’s author, Senator Ed Hernandez (D-Azusa), decided to withdraw the bill.

“I introduced SB 1010 with the intention of shedding light on the reasons precipitating skyrocketing drug prices,” Sen Hernandez said in a statement. “After consulting with a broad coalition of working families, health advocates, health care providers, businesses, community organizations, and many others, I have decided to delay moving this legislation forward.”

The decision is a major victory for pharmaceutical companies, but the battle isn’t over.

A New Bill: VA PRICES FOR ALL?

California residents will be deciding on a separate but related ballot initiative in November that seeks to prevent state-funded health programs such as Medicaid from paying more for prescription drugs than the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

The VA’s negotiating power allows it to obtain some of the lowest rates for drugs — only about 42% of the list price for brand name drugs, on average. California’s Proposition 61, called the Drug Price Relief Act, is intended to capitalize on that buying power.

Whereas SB 1010 had broad support, this ballot measure is a bit more complex, Mr Stremikis explained. There are several other groups that are supportive of the measure’s intent but disagree on the language and foresee the potential for unintended consequences if the bill is passed into law.

For example, patient advocacy groups have expressed concern that the measure could wind up undermining the VA’s protections. Presumably, drug companies only offer the VA such low prices because they are confident they will only have to offer the discounts to veterans. A common concern is that if drug companies are forced to lower prices for state programs, it could cause those same companies to increase the costs charged to the VA.

The pharmaceutical industry has come out in full force against the measure to help ensure California does not set a precedent. Drug companies have given more than $70 million to the opposition campaign, and the LA Times cited estimates that the industry will spend upwards of $100 million by the time the measure is voted on.

The Uncertain Path Ahead

“Drug prices are not an incidental cost of health care in an increasingly chronic care management environment,” said Cindy Ehnes, JD, executive vice president of COPE Health Solutions and an attorney who previously served as director of the California Department of Managed Health Care. “They are a major driver of the increases in the underlying cost of health care in the United States.”

The ability of the health care dollar to absorb these kinds of cost hikes has diminished, she added, particularly because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Under the ACA, there are influences that will counter price increases, but prescription drug prices operate as “an indispensable free radical” within that system.

As some providers look to become accountable care organizations or engage in value-based purchasing contracts, the problem they commonly face is whether or not they can assume the financial responsibility for prescription drugs and meaningfully manage those costs, particularly in light of the volatility and magnitude of cost increases, she explained. It’s a major obstacle to any meaningful health reform that seeks to lower prices to a sustainable level.

“The inability to assume prescription drug costs and manage those costs within a care management program absolutely means that it will be very hard for the system to achieve the kind of ‘triple aim’ goal that is the cornerstone of current health policy in the United States,” Ms Ehnes said.

While it is apparent that a movement is underway to seek out increased transparency in prescription drug pricing and attempt to curb price spikes, what is not yet clear is whether mandates by state legislators or ballot initiates like those seen in California will actually lead to lower drug prices.

From Ms Ehnes’s vantage point, while California’s efforts to implement market and regulatory pressure are laudable, these types of initiatives would ultimately have little impact on drug manufacturers and their ability to set prices as they wish, pointing to the VA ballot initiative as a case in point.

One of the ways the VA is able to get better pricing is by limiting the types of drugs it offers and limiting those who can be placed on the formulary, she said. When purchasing for its Medicaid program, however, the state of California deals with a much broader range of drugs and does not use that same type of formulary, which means the ballot initiative would only impact a subset of drugs.

“So your best case scenario is that the manufacturers lower their prices to the state for those drugs that are on the VA formulary,” Ms Ehnes said. “And that’s a limited impact.”

Meanwhile, Mr Stremikis anticipates that efforts to deal with this issue will continue to march forward regardless of the short-term outcomes experienced in California.

“I think both in California and across the nation we’ll continue to see legislative and regulatory action in this space,” he concluded.