Biosimilars—What`s In A Name?

What’s in a name? When it comes to biosimilar biologic drug therapies, the answer should be simplicity—in the name of safety. So says the AMCP and a number of like-minded groups. They are making it clear to the FDA that the proposal to add a suffix to a product’s traditional International Nonproprietary Name (INN) is an unnecessary and unwise modifier.

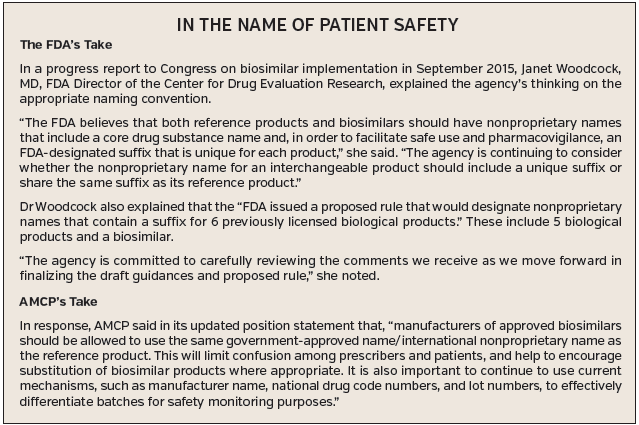

The FDA’s draft guidance calls for “an FDA designated suffix” for both reference products and biosimilars “in order to facilitate safe use and pharmacovigilance,” Janet Woodcock, MD, the agency’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation Research, recently told Congress. She went on to say that whether each should carry a unique suffix or share one remains under consideration. (See the accompanying sidebar for more information about the FDA’s proposal and AMCP’s formal response).

MAXIMIZING OPPORTUNITY WHILE ENSURING SAFETY

Of course managed care stakeholders share the FDA’s commitment to patient safety, but many are questioning if the agency’s move would add a confusing layer to the system, which they believe might present its own set of safety issues.

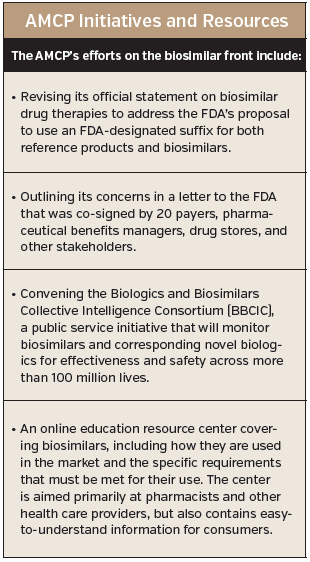

For that reason, AMCP is aggressively making the managed care industry’s position known (see the accompanying sidebar).

The key point AMCP and others are attempting to drive home is this: The health care industry and many of its stakeholders—including patients—are about to enter an era laden with opportunity, thanks to biosimilars. These drugs are projected to exponentially amplify the health care system’s ability to deliver safe value-based care, with savings of as much as $108 billion over 10 years by some estimates. AMCP is out to make sure that nothing—including possible drug name confusion—hampers that potential.

First Report Managed Care recently caught up with Mary Jo Carden, RPh, JD, AMCP’s vice president of government and pharmacy affairs, to learn more about the group’s efforts, dive deeper into the issue, and discuss a possible alternative.

CONSIDER REAL WORLD PRACTICE

For starters, Carden wonders if the FDA’s proposal fully considers the way medications are actually delivered at the practice level. “Within drug databases when you do programming and add to a product name, that might not be something people are familiar with. Even if they are, they are reading a lot of information, and they may not look at the suffix, so it will likely get dropped quite a bit. At the end of the day, we think the suffix is not necessary for product identification, and adds another piece of confusing information that may result in incorrect medications being dispensed or administered.”

Carden used a non-biosimilar drug, Prozac, as an example to demonstrate how patients are aware of what kind of drug they are taking home. “Right now, when a consumer gets a prescription for Prozac, pharmacists in many states have to fill it with the generic fluoxetine.” The standard generic name—without a prefix or a suffix—is clearly stated on the label, along with the manufacturer or distributor name, and the consumer knows what it is, she explained. They do not need an additional identifier. This same strategy, she said, can be applied to biosimilars.

Meanwhile, from a pharmacy perspective, the FDA “Purple Book” will help pharmacists determine if a particular biological product has been designated by the FDA to be biosimilar to or interchangeable with a reference biological product (much the same way the “Orange Book” establishes whether generic drugs may be automatically substituted or whether a pharmacist must contact the prescriber before making a substitution). Carden added that pharmacists also use national drug codes (NDCs) to identify the product, package, and package size. She said that AMCP wants to expand the use of NDCs as identifiers for all prescriptions administered and dispensed in any setting.

USING NDCs IN PHYSICIAN OFFICES

“This is a very important piece to keep in mind,” she noted. Though it was not always the case, “NDCs are now required in pharmacy claims to dispense the product. We feel it is a better way of identifying the product to ensure patient safety.”

For that reason, AMCP is exploring the use of NDCs with Medicare Part B claims for physicians’ offices. “Currently, this does not consistently happen, but it would be a better solution than providing [physicians with suffixes] that really do not provide clarity,” said Carden.

From a safety perspective, when there’s a problem with a drug, it is important to get to the root of the issue as quickly as possible. FDA and AMCP agree on this. “Currently, if there is a problem with a drug, there may not be clarity as to which product is actually causing the problem—because the physician is not recording the NDC. But what if we can get more active surveillance that is generated through information sharing between physicians and pharmacies using the NDC? That’s how you get good information quickly about what is going on.”

LOOKING TO EUROPE

Adding suffixes and programming the IT system to recognize those codes is not necessary in the AMCP’s estimation. Carden pointed out that there are already issues with referencing Granix (tbo-filgrastim). “We have heard that the ‘tbo’ has been getting cleaved off in computer systems in some cases.”

And lest anyone think the AMCP’s proposed solution is not tested, Carden suggests looking across the Atlantic. “It’s been done this way in Europe for more than 10 years. They use the INN [international nonproprietary names] successfully.” Additionally, she reiterated that in the US, authorized generics and even generics that have a different formulation from the branded drug don’t necessarily have a different INN, so why differ the name for biosimilars?

AMCP is also concerned that the FDA proposal “provides no realistic approach for the naming of interchangeable biosimilars,” according to a letter it sent to the agency. “There is no real plan to address retrospective naming,” which will result in the potential for multiple labels for a single product, explained Carden. “That will create a lot of problems and lead to a number of issues that could take years to rectify.”

REALLOCATING MISPLACED EMPHASIS

The bottom line is that the potential savings and opportunity to offer value-based care is at risk of being hamstrung because of emphasis on what amount to minor differences between biosimilars and originator products, she explained. AMCP is concerned that the proposed naming convention will convey

to consumers and providers that there are vast differences between biosimilars and original biological products, which could potentially lead to underuse.

“We acknowledge that there are minor differences,” said Carden. “But the important questions we need to answer are (1) is [a biosimilar] appropriate to use in a patient and (2) does it provide a lower-cost alternative? Let’s tackle those issues, rather than playing the name game.”