The Arrival of Gene Therapy: Will High Prices Force Payment Innovation?

Emily Whitehead stood on death’s doorstep at the age of 6 as she battled acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer. Although many are cured following standard treatment, some—like Whitehead— have a form of the disease that resists chemotherapy. After relapsing twice following her 2010 diagnosis, she had seemingly run out of options.

But in 2012, she became the first pediatric patient to receive a new experimental gene therapy at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Despite the barrage of severe side effects, she emerged cancer free as The New York Times reported that year and has remained so for over half a decade now, according to more recent accounts.

The treatment that saved her life was initially developed by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and was a precursor to Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel; Novartis), the treatment that became the first cell-based gene therapy approved by the FDA in August.

Kymriah essentially trains a patient’s immune system cells to attack the cancer and has shown incredible promise for those with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia that has relapsed or resisted standard treatment. In a clinical trial of 63 pediatric and young adult patients, 83% experienced remission within 3 months.

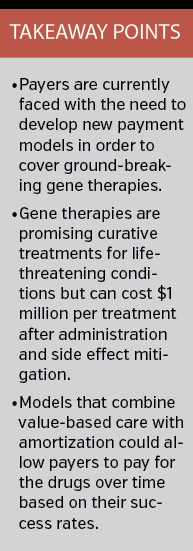

That incredible promise comes at an incredible expense, however. Novartis has indicated that the one-time treatment will run at a fee of $475,000, which has raised plenty of eyebrows and questions about how patients and payers will manage to cover the steep cost. Additionally, the need for continuous monitoring and treatment of severe side effects could push the total cost for treatment above $1 million per patient.

Society Could Pay Twice

Patients who do not respond to treatment within 1 month would not be charged, according to a Novartis press release, and the company has noted that it is taking steps to provide financial help to uninsured or underinsured families.

“The approval of Kymriah by the FDA is a very important milestone because it is the first of a new class of therapies that can mean the difference, really, for many patients between life and death,” David Mitchell, founder and president of Patients For Affordable Drugs, said in an interview.

Even so, he views the price as excessive. American taxpayers have invested over $200 million in CAR-T’s discovery going back to the early 1990s, he pointed out, and even the seminal paper published in 2011 by University of Pennsylvania researchers that demonstrated the therapy would work was funded in part by NIH.

It was only after this high-risk investment of hundreds of millions of dollars and after the viability of the treatment had been demonstrated that Novartis moved to purchase the rights and commercialize the drug. The company also received a 50% tax break on clinical trial costs under the Orphan Drug Act, according to Mr Mitchell, and was awarded a priority review voucher by the FDA.

“The level of taxpayer investment in this new Novartis drug is demonstrably high, and we believe that it should be priced in light of that investment,” he said. “Instead, we believe Novartis has priced the drug at least $150,000 per treatment too high.” That figure, he explained, takes into account the ability for Novartis to maintain its historically claimed R&D expenditures and levels of profit.

What some see as excessive, though, others see as reasonable. Kymriah is a fundamental disruption in the practice of medicine and the provision of health care, said Michael Werner, JD, executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, and it changes the paradigm of health care in the United States.

From his vantage point, a gene therapy should be priced based on its value to the patient and society.

“By providing a transformative therapy in a single administration, potentially curing disease, it’s not only giving someone their life back but it’s also defraying other kinds of health care costs to the system,” Mr Werner said.

In the case of Kymriah, there is a deadly condition associated with an already large spend, Steven Miller, MD, chief medical officer of Express Scripts told First Report Managed Care in October. Chemotherapy and stem cell transplants often amount to up to $400,000, and the survival rate is still less than 50%. At $475,000, the new therapy for childhood leukemia is priced at a premium, he said, but it’s a well-deserved premium considering the jump in survival rate.

In an editorial in JAMA, Peter B Bach, MD, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, warned against branding gene therapies for cancer as cures until enough data become available.

“The term cure will connote to some patients that a single infusion of this scientifically mystifying, genetically driven therapy will first vanquish their disease and then reset their life expectancy to normal,” Dr Bach and colleagues wrote. “Perhaps one day data will support such a hope; as of yet the available data are insufficient to claim much more than CAR-T treatments have large promise at an enormous price.”

Article continues on page 2

Tip of the Iceberg

The first FDA-approved commercial gene therapy will undoubtedly present a sizable financial conundrum for the current health care system. However; the more significant problem comes with the realization that this is just the beginning.

“Kymriah is just the tip of the iceberg of a whole wave of new technologies and products that we’re going to see come to the forefront over the next few years,” Mr Werner said.

There are hundreds of gene therapies for cancers, genetic disorders, and infectious diseases now in clinical trials and dozens in the most advanced stage of testing. The movement is a shift in the way illness will be treated as many of these promise to be outright cures using a single injection or procedure. It is also forcing the health care system to reconsider the way medicine is paid for.

“Our concern is both for the individual patients and their families but also the fact that our system will buckle under the weight of drugs this expensive when you think that there are 60 or 70 more in stage three clinical trials coming right behind,” Mr Mitchell noted.

And yet, in some cases, these treatments could, arguably, be a better deal than those currently available considering the cost of treating some medical conditions can pile up over time. An MIT Technology Review report looked at the numbers and offered up several examples:

• A 2009 study in the American Journal of Hematology found that the average annual cost of health care for patients suffering from sickle cell disease ranged from $10,704 for children up to 9 years old to $34,266 for those 30 to 39 years old. Lifetime health care costs for a 45 year old with sickle cell disease reached $953,640.

• Hemophilia requires regular injections of clotting factor, which can cost tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. A 2016 study in the American Journal of Managed Care found that the average annual cost per patient for men with hemophilia was $155,136.

• A bone marrow transplant offers a cure for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and the disease can be managed with enzyme replacement therapies, but GlaxoSmithKline has indicated that expenses can total over $4 million for a single patient over the span of a decade.

Gene therapies are beginning to offer a new approach for these conditions and a variety of others. Bluebird Bio has announced that its experimental gene therapy cured a teenage boy with sickle cell disease, according to the MIT Technology Review report, and clinical trial results from Spark Therapeutics have revealed that gene therapy can cure hemophilia B. Beyond that, a gene therapy for SCID, marketed as Strimvelis by GlaxoSmithKline, is already available in Europe.

New Payment Models Needed

Despite the promise of Kymriah, the sticker shock is enough to give payers plenty of pause and it is not yet clear whether insurers will cover the therapy.

Additionally, recent reports indiacte that the $475,000 price tag is only an initial cost for a Kymriah gene therapy treatment, which after adminstration, monitoring, and mitiagtion for severe side effects could double its total cost—adding up to almost $1 million per treatment.

Appropriate patient selection would be one key to making sure dollars are being used wisely to achieve the best clinical outcomes, Dr Miller explained. This type of utilization management is already used for a variety of other high-priced products, such as hemophilia treatments and enzyme replacement therapies, to ensure that the right patient is being treated with the right methodology through the right provider.

Even so, the health care system and its current economic model just is not set up for high priced, one-time treatments, he said. There will be a need to explore new possibilities and modernize the existing reimbursement system using tactics like amortizing the cost over time or creating value-based contracting.

After all, gene therapy trials have not followed patients for a long enough duration to know if they do, in fact, provide a durable cure. If the product does not work as billed and loses effectiveness over time, value-based contracting would ensure the pharmaceutical manufacturers and biotech companies share the risk along with the payer community.

But new ideas also raise some important questions. If a patient switches from one carrier to another, for example, who is on the hook for those downstream payments?

Despite the hefty challenge of that task, Dr Miller remains optimistic. “I really believe gene therapy is here, it’s going to work, and we need to make these products available to patients because it’s truly a great advance forward,” he added.

And just like the biotech and pharmaceutical companies are being innovative, payers will need to innovate and arrive at new solutions.

“We can’t allow these products to fail just because we can’t figure out how to pay for them,” Dr Miller warned.