A Reflective Narrative: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on EP

Dr. Tamirisa shares some of the lessons learned during the pandemic, including the key challenges that COVID-19 presented in the EP field.

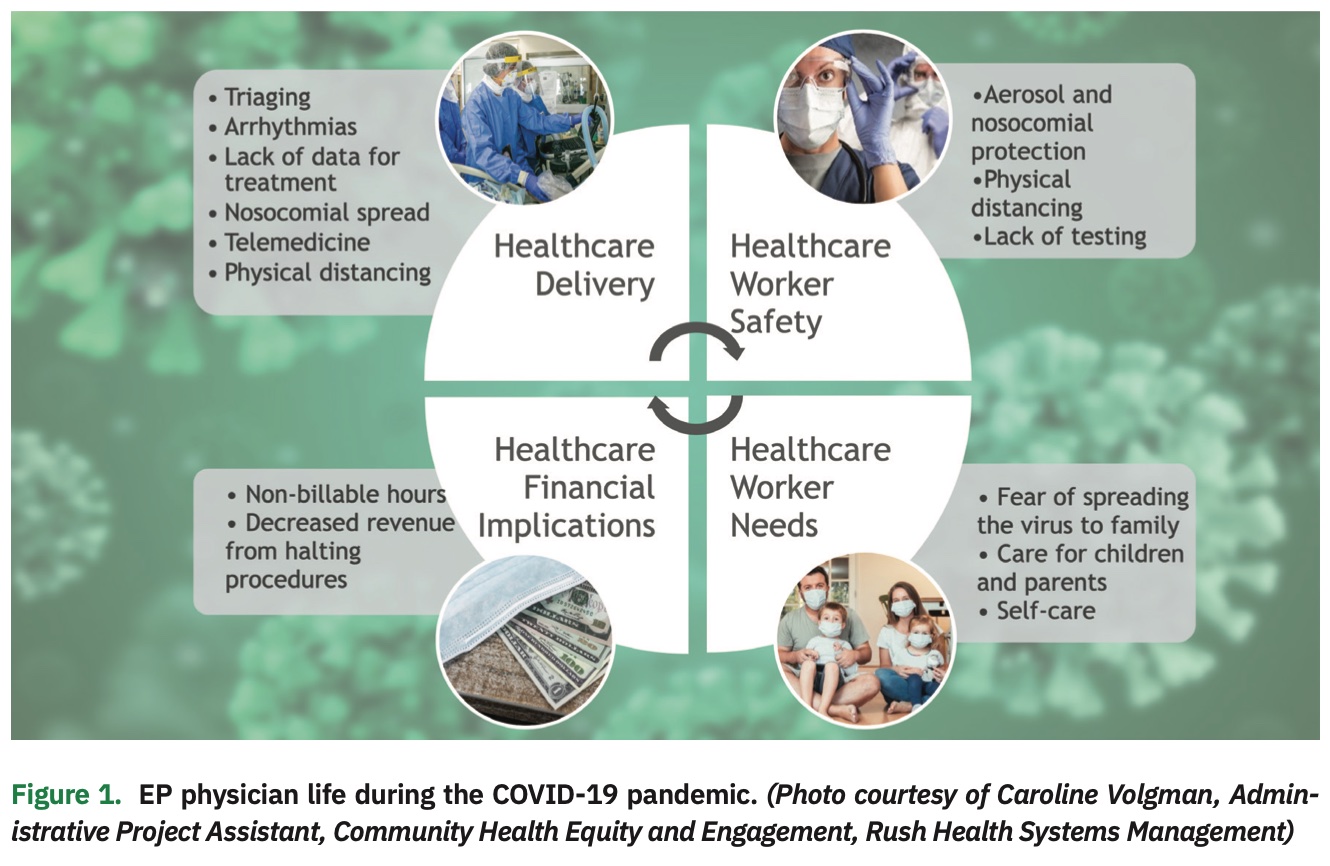

COVID-19 placed unprecedented stress on cardiovascular care.

COVID-19 infection is associated with a number of deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system, including myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and acute myocardial injury.1 Arrhythmias were noted in 16.7% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and nearly 45% of ICU patients with COVID-19.2 Ventricular arrhythmias were also noted at a higher rate in ICU patients with COVID-19.2 Several factors triggered arrhythmias, including inflammation, electrolyte imbalances, hypoxia, myocardial injury, underlying channelopathies, and coexisting CV risk factors.3,4 Thus, the pandemic had a significant impact on cardiovascular care.

As a result of the pandemic, we expanded our skills beyond our comfort zone (eg, mapping, ablating, implanting, and extracting) in the EP lab.

Until the pandemic, the primary ID (Infectious Disease) focus in our EP lab had been on CIED infection and management. With COVID-19, consideration of aerosol and droplet risk became an integral part of our collaborative decision making in the EP lab. In an effort to mitigate the nosocomial spread of the virus, we took measures to avoid intubations in the lab. Transesophageal echocardiograms (TEEs) became one of the highest risk procedures and were avoided unless there were no other options. When doing procedures on COVID-19-positive patients, protecting our staff and anesthesia colleagues was a top priority. Procedures on COVID-19-positive patients were also scheduled at the end of the day to allow enough time for terminal cleaning. Despite pandemic-related challenges, we were successful in reducing infection risk without losing focus of the patient on the table.

COVID-19 had a direct impact on which elective, semi-urgent, and urgent procedures should proceed.

The pandemic forced healthcare providers to carefully plan their utilization of limited healthcare resources, including rationing personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, and ICU beds. We used the guidelines published by the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force5 in the context of our hospital resources and regional COVID-19 numbers. However, we sometimes struggled to draw a definite line between these categories in a practical approach. Clinical scenarios could quickly change from good to worse, and the burden of triaging EP patients often left us overwhelmed. At times, our patients were afraid to come for scheduled procedures due to fear of “catching” COVID-19 in healthcare facilities. In some instances, our procedural volumes fell substantially, which meant reduced procedures for trainees in academia, decreased staff work hours, and concerns about potential staff layoff. Regular or periodic COVID-19 screening of patients and staff would have been an ideal solution, but it was not initially available. Our group at Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Institute (TCAI) advocated for COVID-19 testing for physicians, staff, and patients to prevent nosocomial spread and perform procedures in a timely manner. Under Dr. Andrea Natale’s leadership, this was finally implemented using Abbott’s ID NOW rapid COVID-19 test after internal validation testing on 46 patients (97.8% positive correlation and 100% negative correlation).6 Apart from caring for our patients safely and efficiently, we were able to successfully host EP Live, an international live case conference with nearly 1200 attendees. While the event was virtual, our faculty performing the procedures and patients could be in the labs without concern.

As clinical data in COVID-19 patients was initially sparse, dynamic decisions had to be made in care.

Due to limited initial knowledge about COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic, healthcare providers had to make decisions in care based on what was known at the time. For example, was it better to implant an ICD in a COVID-19-positive cardiomyopathy patient before discharge, or wait and prescribe a wearable defibrillator in the interim period? Should cardiac MRI be used to assess scar burden to predict recovery in these patients? Monitoring QTc interval in patients with COVID-19, especially with lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine therapy, led to protocols to mitigate the risk of drug-induced sudden cardiac death.7,8 Recognizing the subset of patients with propensity towards TdP due to excessive QTc prolongation (congenital LQTS) was imperative, along with aggressive repletion of electrolytes. QTc of >500 msec at baseline or a delta of 60 msec increase from baseline meant odds for TdP were higher and needed “close” monitoring, which had to be done while limiting exposure to COVID-19 patients. “Designated COVID-19” ECG machines or smartphone-enabled apps (eg, AliveCor KardiaMobile) were suggested. Atrial fibrillation (AF) was also common in critically ill patients with COVID-19.9 Even though beta blockers were recommended for rate control of AF with COVID-19,9 drug-drug interactions with anti-viral agents were often seen. Prescribing anticoagulation in patients with AF became very confusing and needed much deliberation between service lines. Most management recommendations were based on expert opinion,10 because the scientific evidence supporting the conventional therapies in this context were rather limited. Our decisions were backed by observational studies. AF and stroke prevention included consideration of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC), D-dimer levels, bleeding events, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Physical distancing did not stop us from finding ways to learn research and serve.

The EP community rose to the challenges presented by COVID-19. For example, the Heart Rhythm Society’s virtual HRS 2020 Science was a huge success, with several exciting and practice-changing, late-breaking clinical trials. TCAI was invited to contribute to COVID-19-related research; comparison of efficacy of rapid PCR tests (sputum or nasopharyngeal) with serology tests in blood samples (CATCH COVID-19) is ongoing.11 In addition, in-person clinical visits were replaced with telemedicine, enabling uninterrupted care for our patients; this continues to this day. Wound checks and remote device checks were also incorporated into telemedicine visits.

The stress, loneliness, and fear experienced by patients in periprocedural isolation as a result of visitor restrictions due to COVID-19 was met with empathy and reassurance to patients by healthcare providers. This meant several hours of “unseen” and non-billable hours, paid back with gratitude from patients and their families. Losing a patient or facing a complication is always hard, and COVID-19-related stress didn’t make this easier by any means.

COVID-19 disrupted our lives, but also left us with many valuable lessons and insights.

COVID-19 affected almost every aspect of our personal lives. Healthcare providers still had their own families to care for. Many of us changed out of our hospital clothes in the garage due to coronavirus concerns. Many of use also had to deal with the nuances of our children’s virtual school. We are still sterilizing our smartphones and keys in UV light. Dual-physician families had the unique concern of both partners potentially contracting the virus or dying. Some of us lost friends and family members to COVID-19, and were forced to grieve from a distance via an incomplete and unnatural FaceTime or Zoom funeral. Grieving for own while continuing to work was not easy, but we found comfort in our duty serving the sick.

We forged on, worked collaboratively, and supported each other, persevering and continuing with the same vigor and compassion as ever before. COVID-19 left us with many valuable insights and made us more skillful navigators in the EP lab and better healthcare providers as well.

On a personal front, I want to thank and acknowledge Dr. Andrea Natale for pushing COVID-19 tests and research, Dr. Amin Al-Ahmad for his unrelenting mentorship, Drs. Rodney Horton and Javier Sanchez for their insightful and kind support, and Medical City Dallas EP Lab Director Dr. Jodie Hurwitz (North Texas Heart Center) for her resounding leadership. I am immensely grateful for my group at the Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Institute.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest to report regarding the content herein.

- Matsushita K, Marchandot B, Jesel L, Ohlmann P, Morel O. Impact of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system: a review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1407. doi:10.3390/jcm9051407

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

- Dherange P, Lang J, Qian P, et al. Arrhythmias and COVID-19: a review. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6(9):1193-1204. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2020.08.002

- Kanthasamy V, Schilling R. Electrophysiology in the era of coronavirus disease 2019. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2020;9(3):167-170. doi:10.15420/aer.2020.32

- Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Gopinathannair R, et al. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):E233-E241. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.03.028

- Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Institute uses Abbott’s ID Now COVID-19 rapid test to screen EP patients. DAIC. Published May 20, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://bit.ly/3chDgGZ

- Giudicessi JR, Noseworthy PA, Friedman PA, Ackerman, MJ. Urgent guidance for navigating and circumventing the QTc-prolonging and torsadenogenic potential of possible pharmacotherapies for coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1213-1221. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.024

- Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2372-2374. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2010419

- Rattanawong P, Shen W, El-Masry H, et al. Guidance on short-term management of atrial fibrillation in coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(14):e017529. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.017529

- Ortega-Paz L, Capodanno D, Montalescot G, Angiolillo DJ. Coronavirus disease 2019–associated thrombosis and coagulopathy: review of the pathophysiological characteristics and implications for antithrombotic management. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(3):e019650. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.019650

- Comparison of the Efficacy of Rapid Tests to Identify COVID-19 Infection (CATCh COVID-19) (CATCH COVID-19). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated August 11, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04372004