ADVERTISEMENT

Thinking Creatively When Approaching Thrombotic Occlusions

An embolus is defined as any substance (natural or unnatural) that can be entrapped within the vasculature of the bloodstream. Emboli of natural causes can be classified as any obstruction of fat deposit, air, or clot that causes a decrease in blood flow to a specific area within the body tissues. Additionally, foreign intravascular object embolization (FIOE) can be more inclusive, involving iatrogenic objects such as: intravascular catheter or wire embolization (ICWE) or an intravascular non-catheter object migration (INCOM), such as surgical stents, filters, and coils. Embolisms can cause a lack of blood flow resulting in tissue death if not retrieved within a short period of time.1

Many different techniques and thrombectomy devices are used to retrieve foreign and/or non-foreign emboli including a guide wire, proximal or distal wire grab techniques, snares, aspiration thrombectomy, or stent retriever thrombectomy techniques.2,3 All these methods are useful in case-specific scenarios. For example, aspiration thrombectomy procedures would be useful for acute thrombotic emboli, and snare techniques would be useful for retrieving embolized peripheral devices such as vascular filters or wires. Each of these techniques and devices should be mastered by angiologists to deter the adverse events caused by emboli. Many of these embolic complications are unexpected, and frequently, the angiologist must use creative methods in order to retrieve these emboli quickly.

In the case herein, we share an instance of thinking ‘outside the box’ in order to endovascularly retrieve foreign emboli. An elderly man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease (with a history of multivessel stenting), and chronic kidney disease presented with bilateral lower extremity pain that was greater in the right leg compared to the left. The patient’s right popliteal artery demonstrated a significant stenosis that was treated via atherectomy; however, upon filter removal distal to the lesion, the filter tip broke and embolized distal to the popliteal artery lesion. The thoughts, techniques, and devices utilized to capture the broken filter are explained below.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old man with a history of multivessel stenting, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease presented with bilateral lower extremity pain that was greater on the right extremity.

An ankle-brachial index (ABI) and duplex ultrasound demonstrated a significant decrease in the right ABI, with moderate to severe right popliteal artery stenosis. Abdominal aortography also confirmed 90% stenosis in the right distal superficial femoral artery (SFA) and right popliteal artery, with calcium noted on angiography (Figure 1).

Intervention

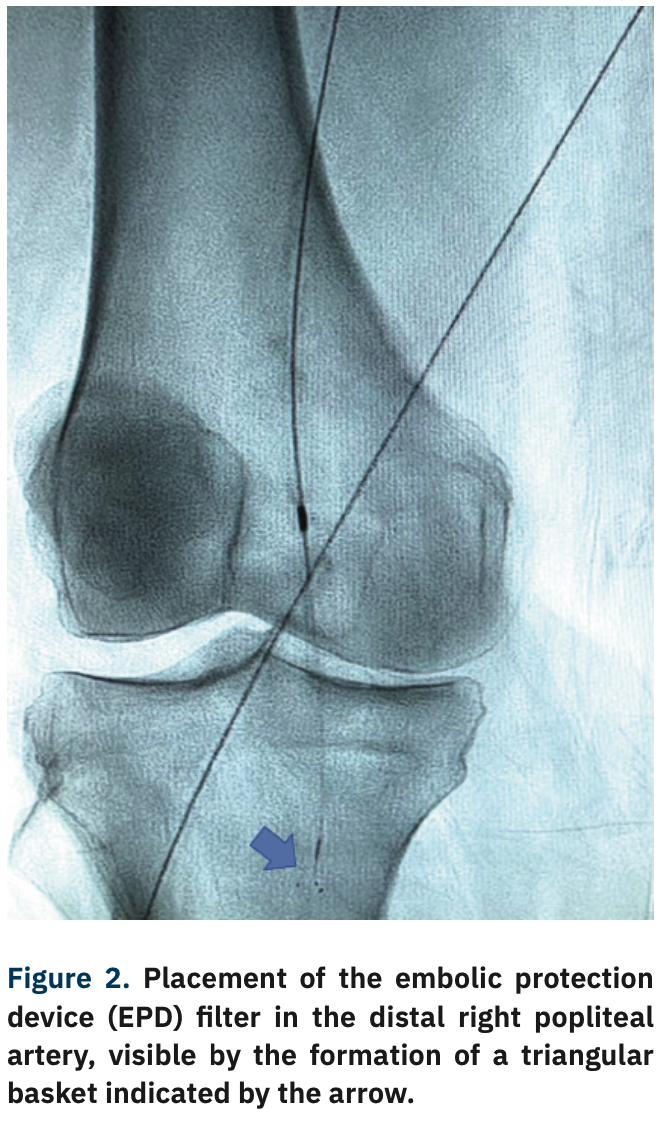

Contralateral retrograde access of the left femoral artery was obtained, and a 6 French (Fr) 45 cm sheath was advanced to the level of the right common femoral artery (CFA). A Mongo wire (Asahi Intecc) was inserted to cross the distal SFA and popliteal lesions. An embolic protection device (EPD) filter was placed in the distal popliteal artery (Figure 2). Orbital atherectomy was performed with a 1.5 solid crown Diamondback (CSI), followed by a 5 mm x 250 mm drug-coated balloon at the lesioned sites (Figure 3).

A complication occurred when removing the EPD filter when the tip broke into the popliteal artery, requiring removal (Figure 4). The Goose Neck loop snare (Medtronic) technique was used to effectively remove the two broken filter pieces (Figure 5). Following removal, final angiogram pictures were obtained, and demonstrated no dissection or perforation of the vessels (Figure 6). The distal SFA and popliteal artery occlusions resolved from 90% stenosis to <20% residual stenosis.

Discussion

Foreign intravascular object embolization (FIOE) is a complex matter that if left untreated can lead to necrotic tissue death and potential limb loss. Even with intervention to remove FIOE, not all methods for emboli removal are as effective and could lead to iatrogenic complications. The case above specifically demonstrates the unique use of the Goose Neck snaring technique and how it can be used in critical scenarios. While other methods may potentially be of use, the optimal choice remained the Goose Neck snare, as it easily retrieved the broken filter and stent in a near-effortless manner. Another technique that may have been used is the trifold loop snare (EN Snare system, Merit Medical), as it functions similarly to the Goose Neck snare with the same effectiveness in retrieving FIOEs.

Having not only a large knowledge base of techniques, but also knowing how to apply these techniques is necessary for the practicing interventionalist. A practitioner lacking in a wide variety of skills may lead to non-optimal occlusion clearance, concurrently increasing the harm done to the patient. Furthermore, medicine is forever changing. This requires that interventionalists be up to date with current literature and become adept in new techniques that develop throughout the years. Mastery of new techniques will not only benefit the angiologist with a wider range of expertise, but can also improve patient outcomes as the practitioner learns to use these skills in a wide range of scenarios.

References

1. Wojda TR, Dingley SD, Wolfe S, Terzian WH, Thomas PG, Vazquez D, Sweeney J, Stawicki SP. Foreign intravascular object embolization and migration: bullets, catheters, wires, stents, filters, and more. In: Firstenberg MS, ed. Anonymous Embolic Diseases: Unusual Therapies and Challenges. 2017. DOI: 10.5772/68039

2. Munich SA, Vakharia K, Levy EI. Overview of mechanical thrombectomy techniques. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:S60-S67.

3. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:888-897.

Disclosures: Dr. Adams reports he is the CMO for Cordis, and a consultant to CSI, Abbott Vascular, Philips, and Boston Scientific. Mr. Tubberville and Ms. Lambrinos report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

The authors can be contacted via George Adams, MD, at george.adams@unchealth.unc.edu